Comedy recipes

While it’s not too difficult to describe, in broad terms, the kind of shift in perspective that comedy creates for us, it’s harder to pin down exactly how it achieves it.

Here is a non-exhaustive list of some well-worn ways to extract comedy from a situation or scene.

Change the rules

Begin with a premise that is patently absurd and develop it logically until it is a force that sucks the rational world into it like a black hole.

This is the start of a Marty Feldman radio sketch that begins with two men at a bus stop:

MAN 1: Evening

MAN 2: Good evening.

MAN 1: It’s a nice evening

MAN 2: Yes, thank god.

MAN 1: You’re welcome.

(Listen to the complete “God” sketch? Click here)

From this point on you’re in undiscovered territory. One character insists he is God and, wouldn’t you know it, by the end of the sketch, has persuaded the other one to take him home in a taxi and put him up in his spare room. The second character represents us; he is the ‘straight man’, if you like, and his capitulation to the premise is naturally also ours. We know it’s absurd but our pleasure derives from seeing the premise work itself out.

A lot of comedy is built on the foundations of an absurd premise and it isn’t always anarchic in its form. Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, for example, is based on the premise of a baby being abandoned in a handbag on a station. Although ostensibly a comedy of manners, it is actually by definition a farce because of the ridiculous premise at its heart.

Comedy Magic

There is something a bit magical about the transformative power of a logic conjured up and set askew in this way. It exerts an irresistible pull. This is why children love conjurors or clowns, they appear to break the mundane laws of the everyday world. They have secret powers that are mysterious and entrancing to the unspoiled imagination of a child.

The simplest and most enduring comedy works in a similar fashion. You can see it in its purest form in the physical knockabout of early cinema. Stan Laurel flicks his thumb and gets a flame on the end of it. Oliver Hardy is scornful; how ridiculous, how silly. Hardy flicks his thumb and the same thing happens – panic and consternation!

There is a force at work here that overturns our sensible reality, but that we understand at a deep and instinctive level. This moment in the film Way Out West; where Laurel and Hardy, under the spell of some music, break into a little soft shoe routine; feels almost as if they are obeying some immutable law.

Repeat as necessary

Children love repetition, as any writer of children’s books will tell you, and there is something in all of us that responds to the “here it comes again” element in comedy. Repetition is another way of reinforcing connections and it is seeing the connection that is crucial to us getting the joke.

The famous Rule of Three is something often talked about in this context. First comes the ‘set-up’, followed by the ‘pay-off’ and then finally the delivery of ‘the cap’. The formula is as old as comedy itself. A running gag, or recurring reference, is also a firm favourite and has the added advantage of building up laughs as it goes.

(For a great example, hear the way Marty Feldman uses repetition in this sketch “Funny He Never Married”)

Richard Lester’s film The Knack is full of subtle comic connections. This scene between Rita Tushingham and a suave shop assistant uses repetition to get its point across.

Escalate

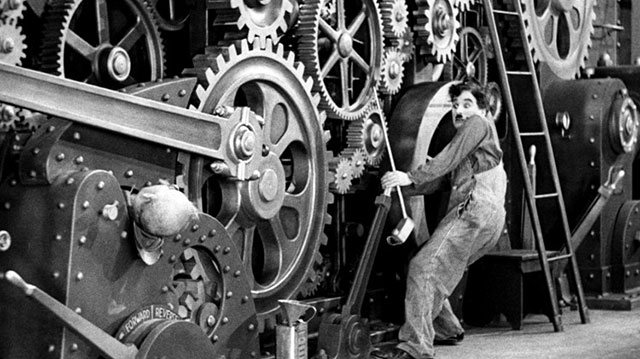

Start small, get bigger. A classic tactic in comedy is to begin with something trivial, the metaphorical flap of a butterfly’s wing, and then build it up until it reaches hurricane proportions. This is the essence of those slapstick routines in silent films and it is humour that has a universal appeal.

The secret of using this technique successfully is to make it consistent but with variations at each stage and to get the timing right. The escalation can be physical or verbal or any combination of the two.

A masterly example of both is this scene between Dom DeLuise and Leo McKern in Sherlock Holmes’ Younger Brother. Here the two bad guys get literally to grips with each other, exhaust themselves, and end tucked up in bed like two toddlers.

Exaggerate and deflate

I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.”

P.G.Wodehouse

Overstate and understate. Using hyperbole, deliberately exaggerated language has long been a staple of comedy from Moliere to Blackadder:

BLACKADDER: Baldrick, I have a very, very, very cunning plan.

BALDRICK: Is it as cunning as a fox what used to be Professor of Cunning at Oxford University but has moved on and is now working for the U.N. at the High Commission of International Cunning Planning?

The added joke here is, of course, the unwieldiness of the language, the deliberately clunky metaphors and similes. But moments of bathos (anticlimax) are just as important in creating comedy.

Here’s an example from the God sketch again:

MAN: I am omnipotent you know; that means “all-powerful”. I have power over all things. I am all powerful, I am omnipotent. There is nothing I cannot do. I can level the mountains, I can turn the seas to Hall’s Tonic Wine. There is nothing I cannot do, I am omnipotent … lend me five bob.

The last line deliberately undercuts and deflates. Alternately, you must be able to think of many sketches and jokes in which God behaves in an off-hand human way. Understatement, like overstatement, works equally well at getting laughs.

This principle can give a humorous twist to even simple statements like ‘Jamie Oliver has slightly more money than God’ or ‘His politics are slightly to the right of Atilla The Hun.’ The word slightly qualifies the exaggeration and amplifies it at the same time. Writers like P.G. Wodehouse, James Thurber and Terry Pratchett employ this type of understatement a lot for comic effect.

Another type of comedy that uses exaggeration is satire. In this scene from Bruce Robinson’s acerbic portrait of the advertising world, How To Get Ahead in Advertising, the excesses of ad-man language are given a wonderfully comic bite.

Wrong words in the wrong place

Change the register (register is a linguistic term that refers to the language appropriate to an occasion). To illustrate how this works: an old sketch was once built on the premise that, due to a foul-up, a set of radio commentators had been given the wrong events to cover.

So the sports announcer is commentating on the Queen’s garden party: “And Lady Devonshire is coming up on the inside and she’s almost got to the cream scones but, wait, look at this, Lady Melbury’s headed her off and she’s there first…” Meanwhile, the fashion announcer is covering the horse races: “Michael is wearing a fetching red blouson as he gallops rather fast towards the finishing line…”

You get the idea. It’s a simple one but there’s still some mileage in it and it’s still frequently used by comedy writers. Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie wrote this typically witty sketch about two lawyers negotiating a first date for a couple (at the time something similar was actually happening at certain Universities in America, couples drawing up contracts before they went out.)

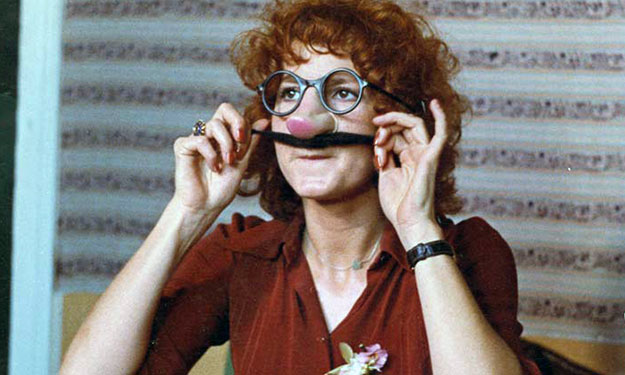

It was also a favourite of the late Marty Feldman who would often take a respected figure like a bishop or a headmaster and change their class and language to create a comic culture shock. Part of the humour, of course, was based on the idea of British reserve in the face of outrageous behaviour: